When we meet Shahzadi Bi in September, she is busy chaining herself to a fence. It’s not just any fence, but the one that surrounds the Chief Minister’s residence in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, where Bhopal is the capital. She is among a group of protesters demanding that the minister keep his promise of providing each survivor of the 1984 gas leak – the more than 570,000 who were exposed – 500,000 Indian rupees (US$8,170) as compensation.

Shahzadi, aged 60, lives in Blue Moon Colony, one of the 22 slums that surround the old pesticide factory formerly owned by Union Carbide India Limited. This area is blighted by water contamination, caused by chemicals from the abandoned factory site.

The disaster overturned her and her family’s lives. “Everyone has dreams,” she says. “I too had those. My dream was not about becoming a teacher or doctor… I wished that we would provide a good education to our children… but the gas leak shattered all these dreams.”

Vomiting and chest pain

Shahzadi, her husband and four children were all afflicted by the 1984 leak. As parents, she says, they were unable to take care of their children in the immediate wake of the disaster because they themselves were incapacitated. Her eldest son and two daughters still suffer from chest pain.

She had two other children after the incident, both of whom are ill. “My daughter couldn’t conceive for four years after her marriage,” she says, noting that it was only after treatment at Sambhavna Clinic, set up especially for Bhopal survivors, that this changed. “Otherwise,” she continues, “doctors had told her clearly that ‘since you have been drinking this toxic water, you will not be able to give birth.”

Her 22-year-old son is unable to do heavy work, she says. “All these problems, such as irritated eyes, kidney failure, respiratory diseases, lung cancers… are found commonly in almost every home of gas victims. This is the situation in all 22 slums.” She adds that women and girls experience problems with their menstrual cycle.

As Shahzadi Bi points out, many people born after the tragedy experienced similar symptoms to those who were exposed to the leak. Local activists say this is a result of being born to gas affected parents as well as being exposed to toxic water.

Despite all these ailments – or perhaps because of them – Shahzadi is now a member of a number of campaigning groups, including the Stationary Workers Association and the Bhopal Gas Victims Struggle Committee.

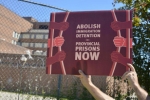

“We did many demonstrations and carried out many rallies, burnt many effigies, sat on hunger strikes, carried out two marches on foot from Bhopal to Delhi, in 2006 and 2008,” explains Shahzadi. “In 2006, we raised the issue of toxicity in ground water of these 22 slums. The government listened to us and agreed to provide us clean water from the Narmada pipeline.”

The clean water didn’t arrive right away – that took another three years and another march to Delhi, too. Still, it’s a significant win in the 30-year campaign.

“Now our struggle is against the injustice meted out to gas victims and victims of toxicity in water,” says Shahzadi.

Long struggle

The Bhopal struggle for justice has been largely led by women. Shahzadi feels that this is because of their unique position in the family. “Women see the pain of our children every single moment,” she says. “That is the reason women feel so attached to the struggle – to better the lives of the next generation.

For these women and for men, too, the struggle has been long and the obstacles many. Activists’ calls are simple, says Shahzadi. They want proper compensation for victims of the gas leak as well as for those affected by water contamination. They also want the government to ensure that the toxic waste that was left behind is cleaned up.

But, she says, survivors can’t do it alone. “If you show solidarity and support, our determination to fight will be boosted. We will not feel alone anymore.”