By Rachel Chhoa-Howard

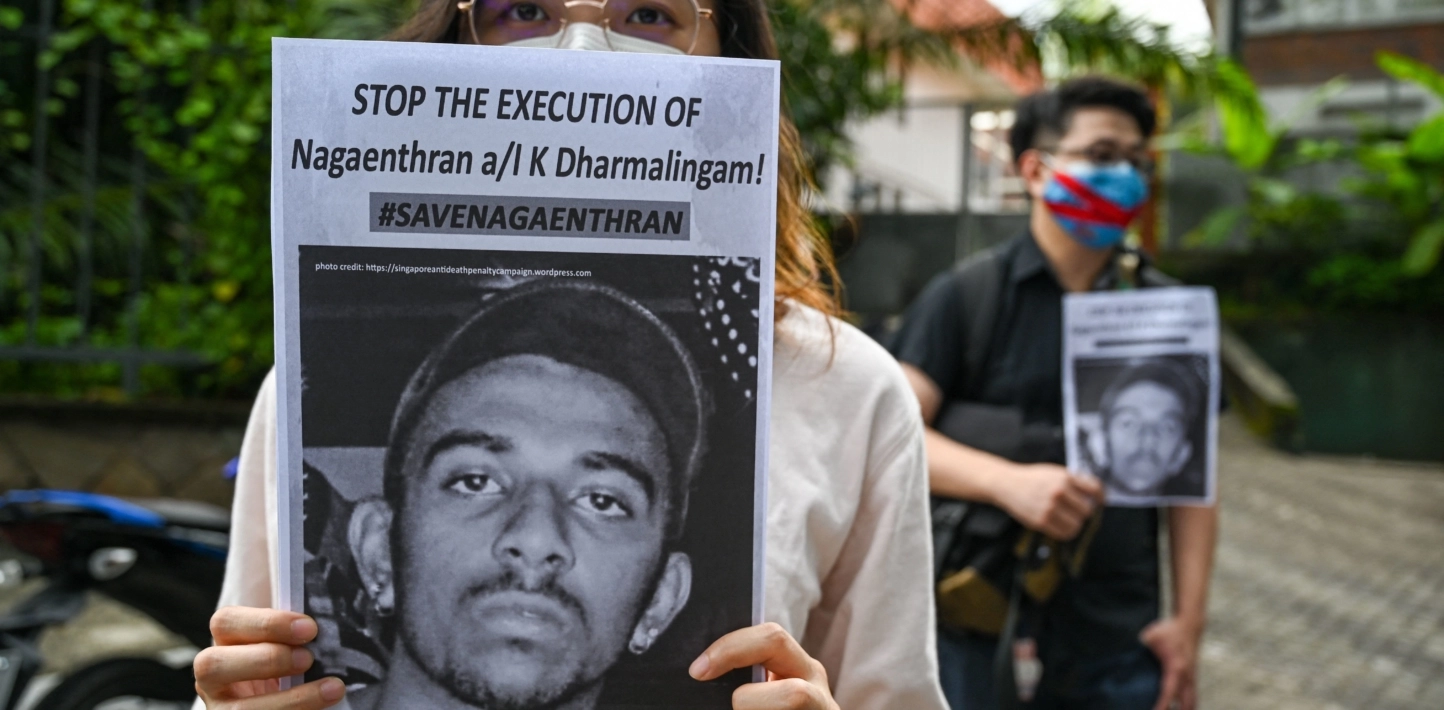

Nagaenthran K Dharmalingam, who is on death row in Singapore, has few chances left.

Over the last few months, the fate of the 34-year-old Malaysian, who is set to be executed by hanging for drug-related offenses, has captured international attention. From experts at the United Nations to British billionaire Richard Branson, who tweeted that the case exposed the “fatal flaws” of the death penalty, to members of the public internationally, tens of thousands have urged for his execution to be called off.

There was collective outrage when, despite medical experts finding that Nagaenthran has an intellectual disability, his family learned that the Singapore authorities had scheduled his execution for 10 November. Concerns mounted when his family reported that his mental condition had deteriorated significantly when they visited him in prison, where he appeared to not fully understand what was happening to him.

The UN body monitoring compliance of the Convention of Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), to which Singapore is a party, has stated that the imposition of the death penalty on people whose mental and intellectual disabilities may have impeded their effective defense is prohibited.

In an unexpected twist, Nagaenthran’s appeal hearing was postponed when he tested positive for Covid-19. However, he has now presumably recovered and his life is again in peril. His appeal hearing has now been re-set to 24 January and, with other legal claims denied, this could be his last chance to be spared execution.

There is still time left for Singapore to change course and prevent a travesty of justice. Authorities should ensure Nagaenthran has a fair hearing and halt his execution, which would be unlawful under international law in light of the numerous flaws in his case. This includes the fact his sentence was imposed as a mandatory punishment and for an offence that does not meet the threshold of the “most serious crimes” to which the use of the death penalty must be restricted under international law.

A significant factor remains Nagaenthran’s intellectual disability and mental health state, which may have severely impacted his right to a fair trial including effective defense, up to these last critical stages.

His intellectual disability would also have impacted his ability to communicate his knowledge of relevant information and his engagement with the authorities, including when questioned by officers of Singapore’s Central Narcotics Bureau, without the presence of a lawyer, after his arrest in 2009 for importing 42.72 grams of heroin.

This in turn might have had a bearing on the information he provided for what’s called a certificate of assistance, which is needed to qualify for sentencing discretion in Singapore – itself a flawed process. In addition, from information on his present mental state, Nagaenthran’s cognitive function appears to have been severely impaired after years in detention.

Accommodation measures as required by international law and guidelines on access to justice for persons with disabilities were not yet built into Singapore procedures when Nagaenthran was arrested in 2009. These may also have spared him the death sentence, and should be applied retrospectively to prevent a terrible injustice from taking place.

There is no evidence that the threat of execution acts as a greater deterrent to crime than life imprisonment, something confirmed in multiple studies, including by the UN, across the globe. Singapore, which regularly tops global indexes for standards of living, lags far behind global sentiment against the death penalty. As of today, the majority of the world’s states have abolished this cruel punishment in law for all crimes. The number of states that have voted in favour of UN General Assembly resolutions calling for a moratorium on executions has consistently increased, from 104 in 2007 to 123 at the most recent vote, in December 2020.

Trends have been shifting in the Asia-Pacific region as well, where 20 countries have abolished the death penalty for all crimes and a further eight are abolitionist in practice. In 2020, six Asia-Pacific countries carried out executions – the lowest number since Amnesty International began keeping records.

Within ASEAN, only five countries in the region − Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, and Viet Nam − have carried out executions in the period 2016-2020, yet no executions have been carried out in Indonesia since 2016 and Malaysia has been observing an official moratorium since 2018.

The Singapore authorities should immediately halt plans to execute Nagaenthran and establish a moratorium on all executions as a critical first step. After global outcry from around the world, the life of a man on death row, and Singapore’s human rights reputation including its treatment of persons with disabilities, are in the balance.

Should the courts fail, Singapore’s leaders must be ready to act. Throughout his 18 years in power, Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s cabinet has not once approved an order for the President to grant clemency. But if there was ever a time to do so, it would be now.

Rachel Chhoa-Howard is a researcher on Southeast Asia for Amnesty International