ISSUES & COUNTRIES

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

Amnesty International is a human rights organization and global movement of more than 10 million people in over 150 countries and territories who campaign for human rights. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded by individuals like you. We believe acting in solidarity and compassion with people everywhere can change our world for the better.

CAMPAIGNS

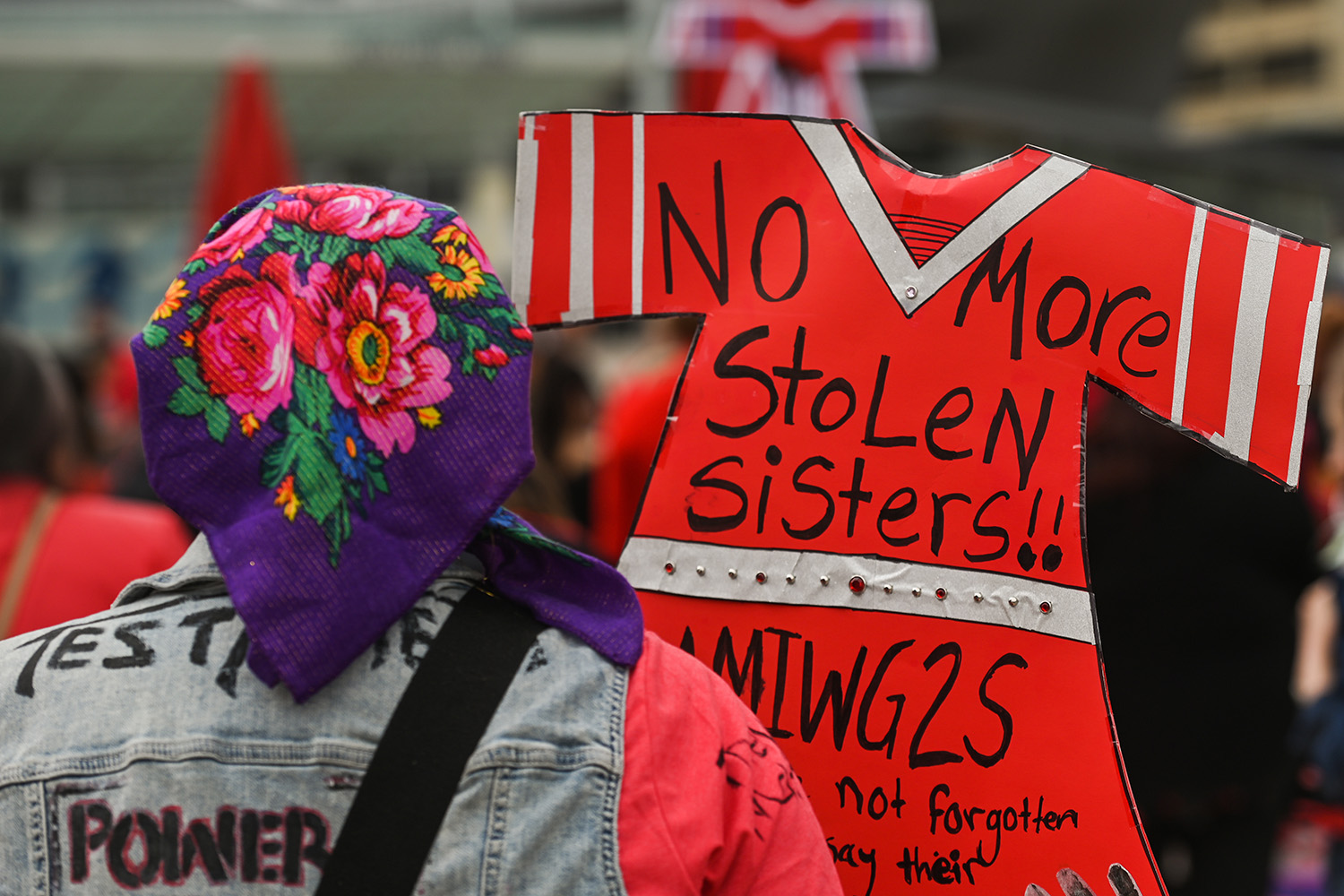

CANADA

WORLDWIDE

REPORTS & PUBLICATIONS

PRESS RELEASES

- Amnesty International Canada condemns Alberta’s use of Notwithstanding Clause to prop up anti-trans policies

- Fossil fuel infrastructure is putting rights of 2 billion people and critical ecosystems at risk

- Sentencing of land defenders sends ‘chilling message’ about Indigenous rights in Canada

- Joint statement: People across Canada demand that Temporary Foreign Worker Program respect migrant workers’ rights and dignity

- Canada: First 100 days of new Parliament signal regression on human rights

PODCAST

Listen to Rights Back at You

We introduce you to fascinating people who are making change unstoppable. Hear powerful stories of resistance and solidarity and learn more about how you can take action now for human rights. This series connects the dots and passes the mic to people building a better future now. Together, we unravel the Canada you think you know and challenge the systems that hold back human rights.