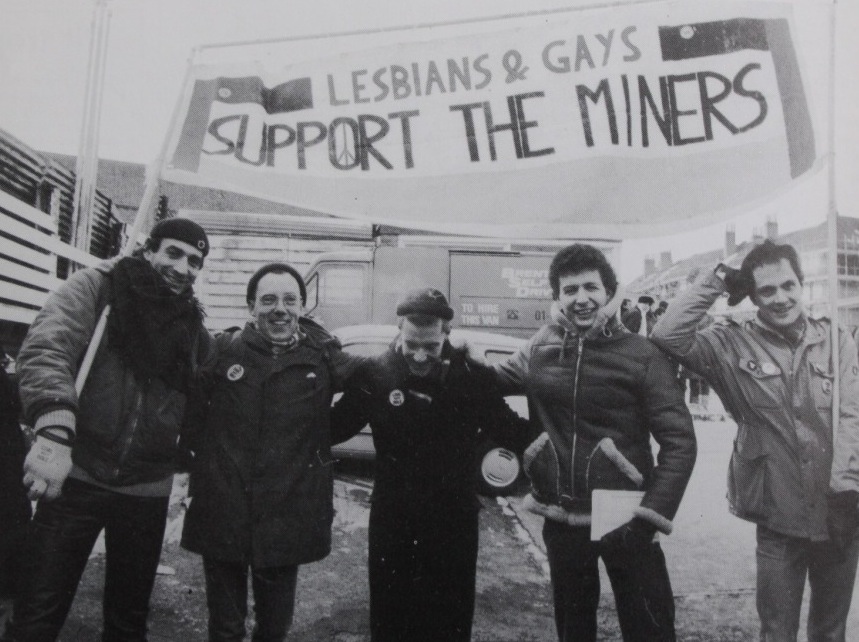

Photo: via www.jacobinmag.com – Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM): an alliance of lesbian and gay men in London (1984/85) who came out in solidarity of the British miners (in Wales) who were on strike. They sought to come together in solidarity around collective experiences of police violence.

This blog is the first in a series of short blogs which will explore some of the different ways we can build meaningful solidarity. I’ve attempted to piece together some of the key articles, opinions, videos and resources that have helped shape my understanding to share, but there is SO much writing and materials on solidarity out there – this will just barely scrape the surface.

Hopefully this is still a useful starting point for moving beyond words – towards practicing and building meaningful solidarity for you in your activism journey.

**Remember:

Important steps in doing solidarity work are: to inform yourself, to take time to reflect, and to be open to be challenged. Some of the material below may challenge your current thoughts or perceptions of solidarity or solidarity work, and I encourage you to seize these learning opportunities.

What is solidarity?

If you google solidarity you might see solidarity defined as:

“unity or agreement of feeling or action, especially among individuals with a common interest; mutual support within a group.”

This is true, however, for solidarity work/ organising to be meaningful and impactful, it should seek to go far beyond just mere support.

Feminist writer bell hooks tells us that:

“Solidarity is not the same as support. To experience solidarity, we must have a community of interests, shared beliefs and goals around which to unite, to build Sisterhood. Support can be occasional. It can be given and just as easily withdrawn. Solidarity requires sustained, ongoing commitment.”

Solidarity work is work. It can be challenging and humbling. It centers on relationship building with affected or frontline groups connecting with people who are affected by the issue/ struggle. Discussions on what it means to practice solidarity are more frequently emerging – with a hope of exploring, reflecting and expanding on individual to collective understandings and experiences of solidarity.

In 2016, AWID (the Association of Women’s Rights in Development) started a campaign exploring what solidarity means for young feminists across gender, racial, economic, social and ecological justice movements. Here’s a beautiful short piece taken from a blog post entitled Solidarity: binding multiple cause, identities and struggles together that was written for the #PracticeSolidarity campaign:

“Solidarity means recognizing the efforts of fellow feminist friends and allies and publicly appreciating their work. It means being curious to learn more about the injustices that my fellow activists face. It means embracing someone’s struggle, as an ally or supporter, even if you haven’t experienced that particular form of oppression. It means stepping back and creating space for more marginalized voices to lead. It means learning to pause and reflect on all that we have accomplished together so far. And it also means taking care of ourselves and others so that we sustain ourselves to continue to show up for each other, until justice for all has been achieved.” – Deepa Ranganathan, a young feminist in India and Frida | Feminist Fund’s Communications Officer, shares her thoughts on #PracticeSolidarity.

To build meaningful solidarity we need to make sure to avoid replicating or reinforcing systems of power and oppression through the approaches that we take. This is why it is really important we inform ourselves about our own power and privilege, which will in turn enable us understand our blind spots and develop strategies for checking our privilege.

Issues and struggles related to power and oppression do not exist in a vacuum, they cannot be separated from the wider systems and contexts which fuel and support them. That’s why when we talk about building meaningful solidarity we need to do more than just acknowledge an issue exists. We need to inform ourselves, reach out to affected communities, build relationships, listen, take action in solidarity with people and collectively tackle the root causes by challenging the systems of power that perpetuate these issues.

Harsha Walia is a South Asian activist and writer based in Vancouver. In her article ‘Moving Beyond a Politics of Solidarity Towards a Practice of Decolonization’ she outlines an example of what meaningful indigenous solidarity organizing looks like which was so eloquently put:

“One of the basic principles of Indigenous solidarity organizing is the notion of taking leadership. According to this principle, non-natives must be accountable and responsive to the experiences, voices, needs, and political perspectives of Indigenous people themselves. From an anti-oppression perspective, meaningful support for Indigenous struggles cannot be directed by non-natives. Taking leadership means being humble and honouring frontline voices of resistance, as well as offering tangible solidarity as needed and requested. Specifically, this translates to taking initiative for self-education about the specific histories of the lands we reside upon, organizing support with the clear guidance and consent of an Indigenous community or group, building long-term relationships of accountability, and never assuming or taking for granted the personal and political trust that non-natives may earn from Indigenous peoples over time.

In offering support to a specific community in their struggle, non-natives should organize with a mandate from the community and an understanding of the parameters of the support that is being sought. Once these guidelines are established, non-natives should be pro-active in offering logistical, fundraising, and campaign support. Clear lines of communication must be maintained and a commitment made for long-term support.

This means not just being present for blockades or in moments of crisis, but instead, activists should sustain a multiplicity of meaningful and diverse relationships on an ongoing basis.”

This is the tip of the iceberg when it comes to answering what is meaningful solidarity? Although, already it’s clear that this is about going beyond words and going beyond tokenism in our approach. It’s hard work, something we need to get better at, and continue to inform ourselves and challenge one another about. We hope to dive deeper into some of the topics touched on here in follow up blogs – so watch this space!

Some questions to reflect on:

(by yourself , with a friend or with your group)

-

What does solidarity mean or look like (to me/ us)?

-

When have (I/ we) practiced meaningful solidarity?

-

Can (I/ we) think of any examples of meaningful solidarity, what are they?

|

In following blogs I hope to explore: allyship, power and privilege, share some concrete examples of meaningful solidarity, as well as a host of further readings, tools and resources that relate to each of these areas towards building meaningful solidarity. Please get in touch: If you have ideas, opinions, resources you’d like to share or if you’d like to collaborate on writing following blogs on any of these topics with me! Contact: Emma Jayne Geraghty – egeraghty[at]amnesty.ca

|