On April 3rd, the Downtown Eastside Women’s Centre (DEWC) in Vancouver released Red Women Rising: Indigenous Women Survivors in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, a report based on the lived experience, leadership, and expertise of Indigenous survivors, which “urgently shifts the lens from pathologizing poverty towards amplifying resistance to and healing from all forms of gendered colonial violence.”

Amnesty International had the privilege of speaking with three of the women involved in producing the report: Carol Martin, Priscillia Tait (Gitxsan/Wetsuweten), and Harsha Walia. Here’s what they shared with us.

READ THE REPORT

What motivated you create this report?

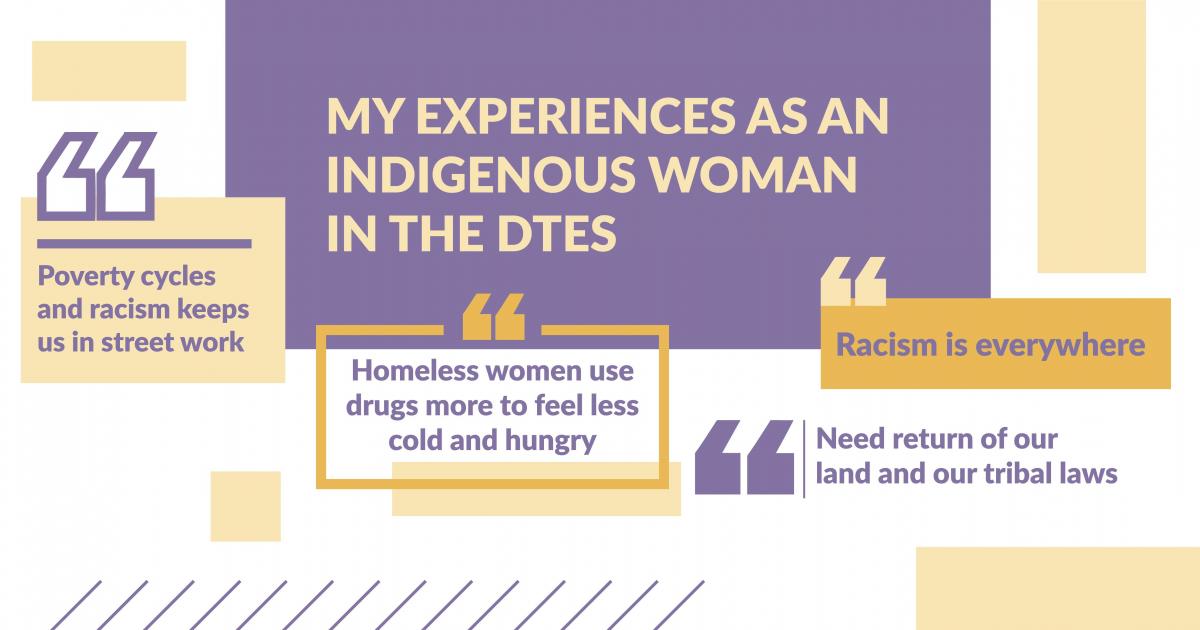

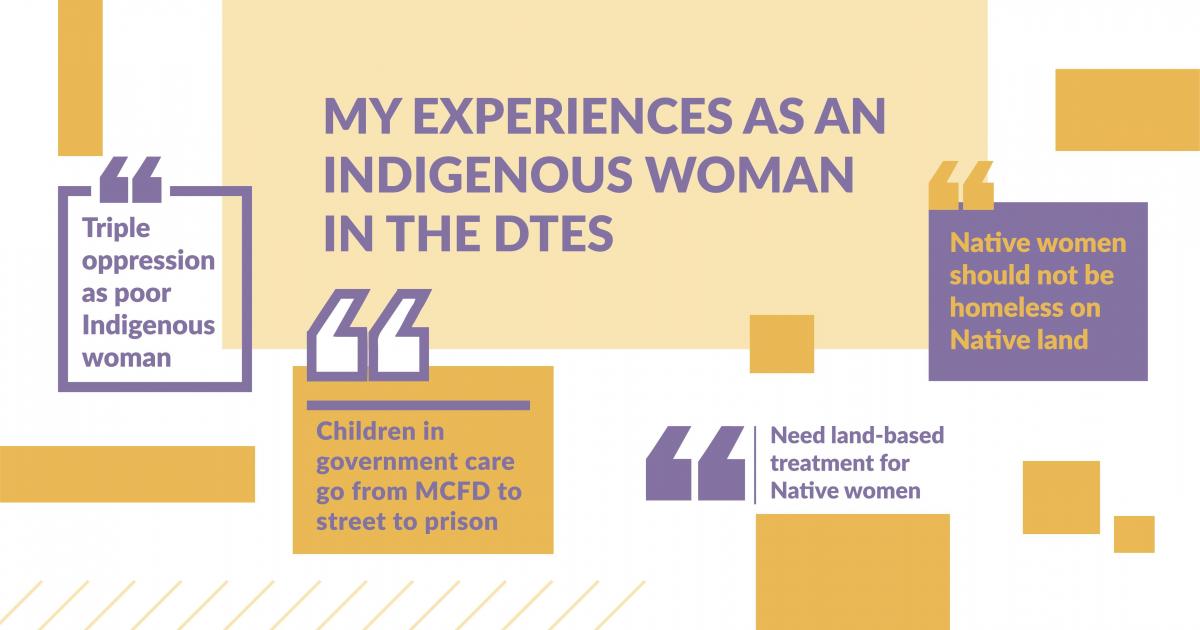

Harsha: There’s been so many reports before. There’s been the provincial inquiry and the recommendations are sitting on a shelf. We asked ourselves what was the most principled way we could approach the National Inquiry, recognizing that we can might create more recommendations that may sit on a shelf? We centered Indigenous women and their diverse methodologies in the report, rather than simply include Indigenous women into a preconceived research model. It wasn’t about hearing from Indigenous women and editing them out. We included what women wanted to say without editing. Over 100 women participated. The report is a transcription of women’s narratives with little editing. Women’s stories were central to the process. We wanted to hear women’s truths. It was led by Indigenous women and Indigenous methodology and grounded by Indigenous elders. The level of insight reflected the trust that was built between the women.

Carol: The National Inquiry was an open door and a platform. Harsha has worked extensively over the years with women finding their voices, and she runs a group for Indigenous women [at the Downtown Eastside Women’s Centre] called Power to Women. When the National Inquiry came around, Harsha recognized that women were ready to run focus groups and extract all the information. They were the leaders and worked with experts from the community. It’s about the women. It’s for the women.

Priscillia: I was asked to spend a couple nights leading a focus group. I felt a strong connection with the women who spoke about their difficulties with housing, because I experienced homelessness myself in 1997 with my one-year-old son, and that’s when I got involved with the Downtown Eastside. It was empowering to hear the women’s voices.

The report is being released less than a month before the final report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls is being submitted to government. What is the significance of this timing?

Carol: The timing is just right. We don’t need the National Inquiry to come out with a report. We already know it because we’ve lived it. I’ve seen how they use our voices and our lives and what we share and it’s all shinied up and filtered to what they think the funders want to hear. This report hasn’t been touched. I’ve seen so much research done in the Downtown Eastside and it just flows through the Downtown Eastside and everyone forgets about it as a one-time thing. A lot of the women who led the groups are great leaders in the community. They get up and do housing rallies, and speak, and are given so much opportunity through the Power of Women group. I keep highlighting it because there’s nothing like it elsewhere. They speak and they rally and they march and they collect stories to be part of a report and this is stuff that doesn’t happen much.

Priscillia: Previous studies have shown little recognition of our artistic potentials. I’m sick and tired of media stereotypes of people in the Downtown Eastside. So many women have these hidden talents. This report will hopefully open up doors to understand the personal trauma that people face and how they use the arts to work through it and to grow. I myself am a community performer. I’ve expressed myself through theatre, dance, photography, and writing.

What is the top message you want that people to take away after reading the report?

Priscillia: That we’re human. And we’re leaders in our own ways. We’re artists expressing ourselves as part of a healing journey. Creating this report is another part of that journey.

Carol: When I think of this report I want people to remove this Canadian lens they have when they think of us. I want them to look at us with different eyes. I want them to read the report with different eyes and different attitudes. What feelings come up when you read this report? Do you have a distaste? Do you have an image of who you think we are?

When you read women’s stories what is happening while you read these? What feelings are coming up? Where do you feel them? Is it in your stomach? When you read a report like this, what does it do to you? If there are negative thoughts write them down and think about where it comes from and ask why do I think this way? We need to start changing people’s attitudes about who we are. That is the feeling of change. Once you feel and acknowledge that, you will make changes in how you look at us.

Priscillia: One of the nights I was facilitating, what really moved me was this one Indigenous woman, who had her personal luggage with her and she was explaining how she had to bring her belongings everywhere with her because she couldn’t leave them at the shelter, and she was having trouble finding housing. I went through a similar experience when I was trying to find accomodation for myself and my one-year-old son. They shut the door because I was Aboriginal and they assumed I was a drug addict and a drunk.

Carol: It’s amazing the strength and resilience of our Indigenous women after everything we’ve gone through. We can relate to everything that everyone says because we’ve all gone through it. Downtown is actually where I found myself. I was part of the Sixties Scoop. I came to Vancouver at age 26 and fell really hard and started drinking. But Downtown with my people is where I found myself and found my strength and resilience. Once you find yourself you could be that light where people can recognize and see things that need to happen in their lives. All the years of labeling and years of making me feel ugly about myself. I used to present myself as a Canadian person, well preserved but empty of my identity and who I am and disconnected from my spirituality and who I was. When I found myself, it was a horrible experience because it was unknown to me and all I felt was ugly and dirty and I felt like a drunk. All the years of hearing that, it took many years to process myself back into my body. Think of all the kids who came home from residential school. This report covers all of that. It takes years and years of knowing each other and trusting each other to come together like this for it to be safe to talk about these things. These are women’s real stories that have been captured in this. Their voices are heard. It’s meaningful.

Priscillia: I grew up with my grandparents, Sarah and Thomas Tait, who survived residential school. What I got from them was my humour, and my desire to help out. I’m not rich but I help out in whatever way I can because that’s what I was taught. There is so much humour in many of the stories I’ve heard from women that I’ve met. They’ve gotten through the pain and the trauma, and the laughter is part of healing too.

Carol: Amidst of all the trust and years of knowing each other, the medicines and our elders were there throughout this whole process, telling the women what the medicine was all about. That’s how healing starts to. Connected to the medicine and who we are, our culture.

Harsha: I think for settlers and non-Indigenous Canadians, often-times we’re constantly presented with stereotypes and statistics and this idea that somehow Indigenous issues are to be addressed by Indigenous people. What this report also does is suggest to settler Canadians that this is fundamentally a Canadian problem. The Downtown Eastside is seen as all about bad statistics, but in fact what’s happening in the Downtown Eastside is an extension of colonialism and gender colonialism. You can’t talk about the Downtown Eastside separate from the rest of Turtle Island. It’s connected to resource development. It’s connected to the Indian Act. It’s connected to dispossession. It’s not an insular neighbourhood.

Indigenous women are not statistics or stereotypes. The recommendations in the report are things that are common knowledge in the neighbourhood. Indigenous women have capacity to contribute to policy discussions about their experiences. There’s 200 recommendations in this report that come from the collective brilliance of Indigenous women in community and decision-makers need to take them seriously and they’re contributing to a national discussion. The National Inquiry wouldn’t have happened without the activism and the care of women in this community.

What message would you like to share with Amnesty supporters who are interested in reading the report and acting in solidarity with women in the Downtown Eastside?

Carol: They need to process questions about if you’re reading something like this, read this over and over until they heal themselves. When you’re reading something what thoughts and images are coming up from you? People need to start paying attention to stories like this. It’s been over 500 years. How long will it take to start changing attitudes and beliefs about who we are. There’s a lot of work to be done.

Priscillia: I just want readers to get to know the women. We are human. The land does not belong to the people, the people belong to the land. Go to your local Aboriginal gathering or centre. Get to know the women on a personal basis. That’s what I want from this report. We’re human and come join us.