Interested in the rights of women in China? Take action in support of Ni Yulan during the Write for Rights letter-writing marathon.

By Lü Pin, Chinese Feminist Activist

The tidal wave of sexual harassment allegations against movie mogul Harvey Weinstein and other powerful men spurred millions of women to speak up online about their disturbing experiences.

Ten years after African American activist Tarana Burke coined #MeToo after meeting a victim of sexual violence, the social media campaign is an unexpected victory for the women’s movement. Due to the bravery of these women the offenders may finally be held to account.

In China, people in power and wider society still struggle to accept that sexual harassment is a major problem. They fail to acknowledge that sexual harassment has a long-term impact on women. Whether it happens in the public or in the workplace, it brings fear, shame and timidity to women, preventing them from enjoying public space and opportunities. Some still blame women’s “improper” behaviour for the men’s actions– at once blaming the victim and denying the issue of sexual harassment as a human rights issue.

After years of work by women’s rights advocates to ignite a mainstream debate on sexual harassment, often in the face of hostility and derision, the Chinese government could no longer ignore the issue.

“After years of work by women’s rights advocates to ignite a mainstream debate on sexual harassment, often in the face of hostility and derision, the Chinese government could no longer ignore the issue.” – Lü Pin

Yet, against this backdrop we have witnessed a victory for women’s rights in China, one that was years in the making.

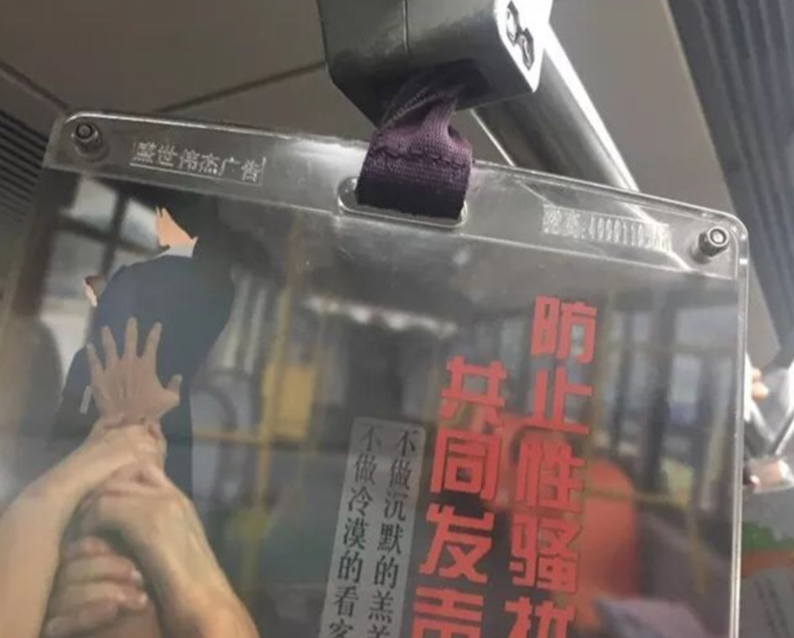

In June 2017, anti-harassment ads appeared in subway stations across Beijing, Shanghai, Chengdu and Shenzhen – in campaigns funded either by corporations or by the government-backed All-China Women’s Federation.

After years of work by women’s rights advocates to ignite a mainstream debate on sexual harassment, often in the face of hostility and derision, the government could no longer ignore the issue.

In March 2015, on the eve of International Women’s Day, five young feminists were detained for planning a campaign against sexual harassment on public transport. The “Feminist Five’ incident rang alarm bells in China. People questioned why campaigning against sexual harassment was banned.

Five years earlier, in 2012 for the first time there was a heated online debate about women’s rights. The question posed was whether a woman is responsible for being harassed if she wears revealing clothing? Some women from Shanghai declared “I can be sexy but you cannot harass me” to clearly express that a woman has rights over her own body. The debate had a long-lasting impact in China: young women became more outspoken about sexual harassment and numerous online debates have taken place ever since.

The “Feminist Five” attempted to redirect this online sentiment into real life activism. The response from the authoritarian government was to ignore the issue and instead suppress the protest. Anti-sexual harassment campaigns organized by civil society became ‘sensitive’ and more risky.

However, the government could not suppress the groundswell of support to end sexual harassment, which grew in scope and strength. A unique phenomenon emerged: public support for women’s rights grew, but activism, which is at the core of the movement, took a backseat.

In 2016, a group of women in Guangzhou, southern China, undertook an online fundraising campaign to fund subway ads against sexual harassment. They waited a year for their ads to be approved, only to be told that government organizations alone can publish such ads.

One of the women involved Zhang Leilei* then took it upon herself to post the ads online. In May 2017, she called for people in different parts of the country to walk around as ‘human billboards’ to raise awareness of sexual harassment. The campaign took off with women and girls across the country posting pictures on social media of the adverts in front of landmarks in their cities. Zhang Leilei’s call for action had given women and girls a channel to air their legitimate grievances and to fight for their own rights.

The successful initiative was abruptly halted by the authorities. The women’s voices were silenced, ignored by China’s mainstream state-run media. Zhang Leilei faced harassment and was forced out of her home.

Zhang paid a high price for her brave activism. While Zhang was left discouraged, ads sponsored by the government or by corporations started to appear on subways, and at least one borrowed words from her campaign.

The government sanctioned campaign is significant because tackling sexual harassment was finally brought into the official public sphere in China. It’s a major first step to including the issue on the public policy agenda. It shows that, however difficult it may seem, change is possible.

Government-backed media outlets even delved into and attempted to take over the feminism discourse. In early 2017, state media outlet the Global Times openly spoke about “official feminism”, suggesting that only the government can tackle concerns of women’s rights. Such forces sometimes take on a more liberal approach, even becoming a voice of justice, but their purpose is only to attract “followers”, luring young people who care about women’s rights but fear social activism to become party loyalists. The fact that China has dropped to 100th in the Global Gender Gap Report shows the ineffectiveness of this “official feminism”.

In an era where civil society is discredited by the government as a hostile force, a movement led by the younger generation, even with its strong public support, cannot garner enough social resources to become sustainable. Activists like Zhang Leilei adapted, eschewing coordinated campaigns. Activism became organic, initiated by one person and echoed by others.

Such groundbreaking activism generated strong public support and the government has heeded these calls. We need to try every means possible and see every failure as energy stored. Uncertainty is high, but in a society where all sense of security has been deprived, every bit of progress becomes a confluence of events.

It was only after decades of tireless advocacy that the anti-domestic violence law was finally enacted in March 2016. By comparison, the discussion on sexual harassment is only at its infancy.

Compared to #MeToo, the anti-sexual harassment campaign in China faces many more hurdles and challenges, but what is most precious and a source for great optimism is that the activists will never give up.

*Zhang LeiLei is a pseudonym