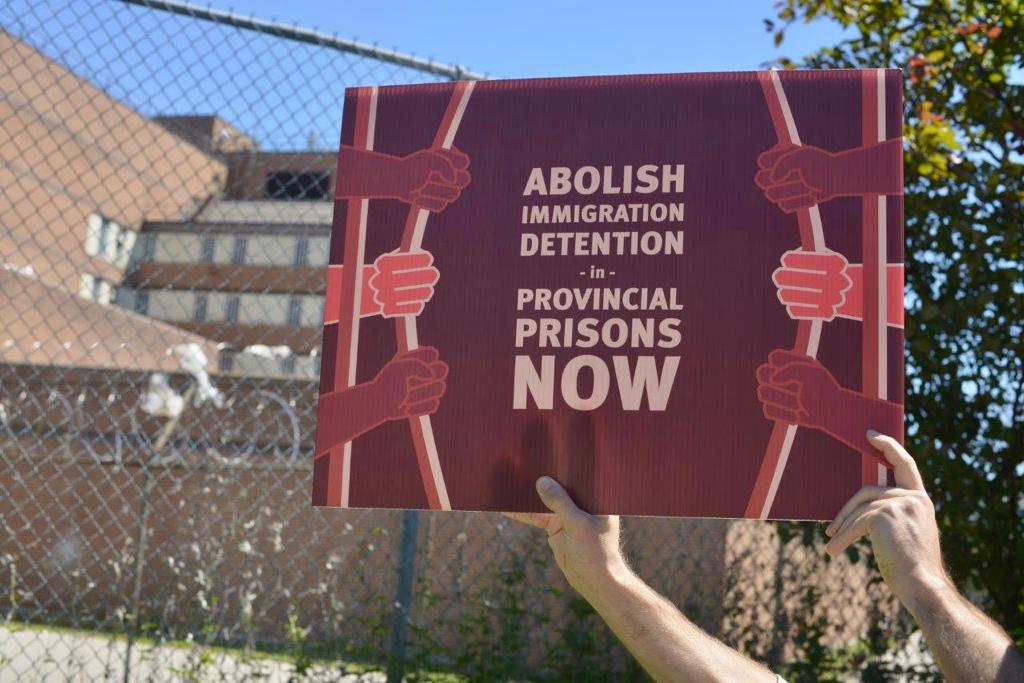

Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and other human rights organizations are calling on the Canadian government to end the practice of immigration detention in provincial prisons, a central recommendation of the jury in the coroner’s inquest into the 2015 death of Abdurahman Ibrahim Hassan.

In a letter sent on Monday to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, Public Safety Minister Marco Mendicino, and Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Sean Fraser, the 40 signatory organizations urged the government to follow the roadmap laid out by the inquest jury, which was tasked with making recommendations to government on how to prevent deaths like Hassan’s from occurring again.

17 deaths in immigration detention since 2000

The coroner’s inquest jury sounded the alarm on Canada’s lethal and discriminatory immigration detention system, in which at least 17 asylum seekers and migrants have died since 2000. The most recent known death in immigration detention occurred on December 25, 2022 in B.C.

‘The death of Abdurahman Ibrahim Hassan has highlighted how racist and discriminatory immigration policies, inadequate support for people with mental illnesses and lack of government transparency threaten the rights — and sometimes the lives — of asylum seekers and migrants.’

Ketty Nivyabandi, Secretary General, Amnesty International Canada

“The death of Abdurahman Ibrahim Hassan has highlighted how racist and discriminatory immigration policies, inadequate support for people with mental illnesses and lack of government transparency threaten the rights — and sometimes the lives — of asylum seekers and migrants,” said Ketty Nivyabandi, Secretary General of Amnesty International Canada’s English-speaking section. “This lethal system must end. We urge the federal and provincial governments, including the Government of Ontario, to heed the lessons of this tragedy and put in place practices that respect human rights and mental health.”

“It is unacceptable that people fleeing violence, conflict, disaster or extreme poverty end up in prisons, including maximum-security facilities,” said France-Isabelle Langlois, Executive Director of Amnistie internationale Canada francophone. “As we have said many times before, it is high time that the federal and Quebec governments put an end to their agreement. Furthermore, Canada should seize this opportunity to put human rights at the heart of its immigration and refugee protection system.”

In 2022, four provinces announced they would end their immigration-detention agreements with the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA): British Columbia, Nova Scotia, Alberta, and Manitoba. When these decisions come into effect, asylum seekers and migrants will not be detained in the four provinces’ prison systems on administrative immigration grounds alone — paving the way for other provinces and the federal government to demonstrate their commitment to human rights by ending immigration detention across the country.

Thousands of arbitrary detentions

In the open letter, the organizations point out that the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) has detained tens of thousands of asylum seekers and migrants on purely administrative grounds. People in immigration detention are subjected to the some of the most restrictive confinement conditions in the country.

In the case of Abdurahman Hassan — a 39-year-old refugee from Somalia with severe mental health conditions who was imprisoned for three years and died in an Ontario prison — the coroner’s inquest revealed shocking details of what people in immigration detention endure, including solitary confinement.

Canada’s practice of detaining asylum seekers and migrants in provincial prisons is a violation of international human rights standards, as imprisonment in these institutions is punitive in nature. It is also highly discriminatory, as detailed in Human Right Watch’s and Amnesty International 2021 report “I Didn’t Feel Like a Human in There” Immigration Detention in Canada and its Impact on Mental Health. Black and other racialized people appear to be detained for longer periods and are often incarcerated in provincial jails rather than in immigration holding centres. In addition, people with mental health conditions are more likely to be subjected to severely coercive treatment, including being held in provincial jails and solitary confinement.

Provinces are complicit in human rights violations against people detained on immigration grounds in their prisons.