Calls to abolish the death penalty in Canada go back to the very founding of Canada in 1867. However, the most concerted efforts in Parliament for abolition can be said to have started with MP Robert Bickerdike in the early twentieth century. Since John Diefenbaker in the 1950s, a long line of Canadian Prime Ministers, both Liberal and Conservative, openly opposed the death penalty with one exception. In 2011, Stephen Harper openly supported the death penalty. When Prime Minister Justin Trudeau succeeded Harper, Canada returned to its tradition of opposing the death penalty in all cases.

Does Canada have the death penalty?

The death penalty in Canada was fully abolished on December 10, 1998. On that date, all remaining references to the death penalty were removed from the National Defence Act. Between 1976 and 1998, the National Defence Act was the only section of the law that still provided for execution under the law.

The last executions in Canada were made under the Criminal Code in 1962 when Ronald Turpin and Arthur Lucas were hanged at Toronto’s Don Jail. The last time the Canadian military had a legal execution was in 1945 when Harold Pringle was shot at dawn in Italy in a controversial murder case (for more, read A Keen Soldier by Andrew Clark, Penguin Random House, 2004).

Since 1867, all civilian executions in Canada were conducted by hanging (military executions were traditionally carried out by shooting). However, there were some unsuccessful experiments with different methods of hanging (i.e. the Radclive gallows) in 1890. The traditional long drop was the standard until the death penalty abolition for ordinary crimes in 1976.

Key Dates

1867 — The Dominion of Canada was founded under the British North America Act.

1945 — The last Canadian military execution

1962 — The last civilian executions

1976 — The death penalty was abolished from the Canadian Criminal Code.

1998 — The death penalty was abolished from the National Defence Act (military law).

2001 — Burns Case

2005 — Canada ratified the Second Optional Protocol [PDF] to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

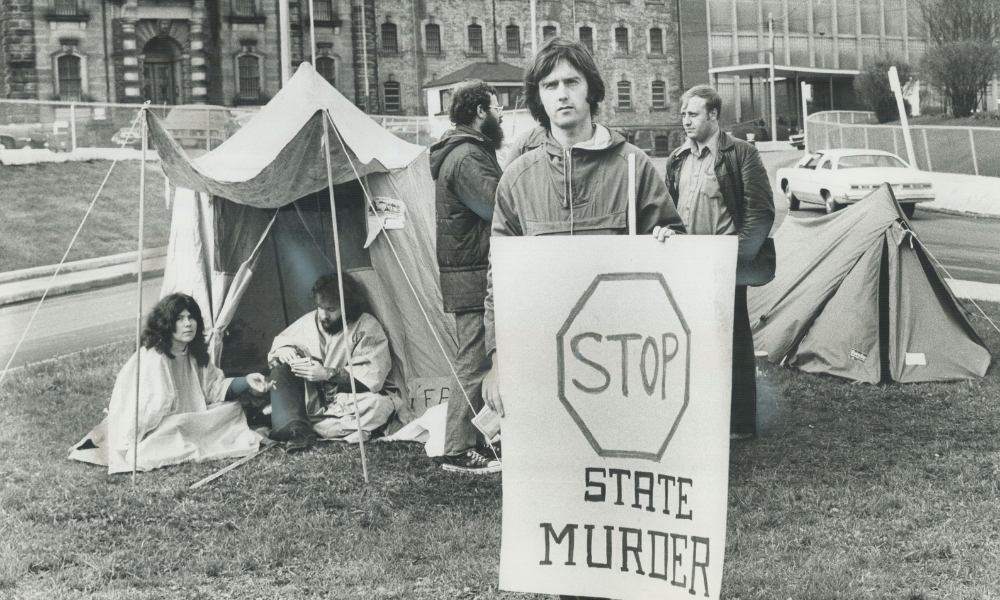

On December 11, 1962, people protest capital punishment outside the Don Jail. (Photo by Barry Philp/Toronto Star via Getty Images)

Canada’s Path to Abolition of the Death Penalty

In 1961, an act of Parliament divided murder into capital and non-capital categories.

The first private bill calling for the abolition of the death penalty was introduced in 1914. In 1954, rape was removed from capital offences. In 1956, a parliamentary committee recommended exempting juvenile offenders from the death penalty and providing expert counsel at all stages of the proceedings and the institution of mandatory appeals in capital cases.

Between 1954 and 1963, a private member’s bill was introduced in each parliamentary session, calling for the abolition of the death penalty. The first major debate on the issue took place in the House of Commons in 1966. Following a lengthy and emotional debate, the government introduced and passed Bill C-168, which limited capital murder to the killing of on-duty police officers and prison guards.

On July 14, 1976, the House of Commons passed Bill C-84 on a free vote, abolishing capital punishment from the Canadian Criminal Code and replacing it with a mandatory life sentence without the possibility of parole for 25 years for all first-degree murders.

Canada retained the death penalty for several military offences, including treason and mutiny. No Canadian soldier had been charged with or executed for a capital crime in over 50 years. On 10 December 1998, the last vestiges of the death penalty in Canada were abolished. Legislation removing all references to capital punishment from the National Defence Act was passed.

The last and final debate in the House of Commons on whether to bring back capital punishment was held in 1987 when the House voted 148-127 against a return to the death penalty.

There were 710 executions in Canada between 1867 and 1962. The last execution was carried out on December 11, 1962, when two men were hanged in Toronto, Ontario. Between 1879 and 1960, there were 438 commutations of death sentences.

The last death sentence passed (and subsequently commuted by abolition) was in 1976. Mario Gauthier, a 19-year-old, was sentenced to death (for more, The Sherbrooke record, 1975-04-21, Collections de BAnQ). He was found guilty of the murder of Georges Nadeau, a painting instructor at Cowansville Penitentiary, where Gauthier had been an inmate.

On May 6, 1975, Holy Cross Father Michael McDonald was one of a group of priests, ministers and others protesting against the death penalty outside the Don Jail. (Photo by Doug Griffin/Toronto Star via Getty Images)

Death Penalty Legally Blocked in Canada

In 2001, the Supreme Court decided in United States v. Burns that it would violate the constitution for Canada to extradite a prisoner who faced a death penalty where destined. In 2005, the Canadian government signed and ratified the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. With no mechanism for withdrawal, this legally prevents any return of the death penalty in Canada.

Canadians are at risk of the death penalty in foreign countries

As a fully abolitionist country, the only Canadians at risk of execution are in foreign countries. Presently, Canadians in China and the United States are at risk of the death penalty.

Before the resumption of principled opposition to all executions, the federal government did not make consistent efforts to prevent the execution of Canadians from 2007 to 2015. While in some cases, such as Hamid Ghassemi-Shall or Canadian Resident Saeed Malekpour, the response was open and strongly opposed to the death sentence. In others, notably Ronald Smith, the government made little if any effort and sometimes only in response to a court judgment ordering effort.

Canada has since 2016 continued to advocate against the death penalty not only for Canadians but for all people.

Amnesty International has been following the cases of at least two Canadians on death row in foreign countries: Ronald Smith (USA – Montana) and Robert Schellenberg (China).

Canada’s leadership on Abolition reborn

In 2007, Canada’s previous leadership in international efforts for abolition crumbled – with a noticeable impact on traditional human rights allies. The long-time government policy to support efforts for clemency for Canadians who faced the death penalty was upended.

Public Safety Minister Stockwell Day announced in parliament that he “…will not actively pursue bringing back to Canada…” those facing the death penalty “…who have been tried in a democratic country that supports the rule of law.” This decision effectively permitted Canada to have a ‘death penalty by proxy’ through countries like the United States. Canada also reversed the previous practice of co-sponsorship of United Nations efforts for universal abolition.

Opposition parties roundly criticized the move. Ronald Smith successfully sued the Canadian government in federal court. The court ordered the federal government to continue to support clemency for Smith, as it had since Smith’s original death sentence in the 1980s.

The change in Canada’s stance in 2016 could not have been clearer. After failing to co-sponsor the UN General Assembly resolutions from 2007 to 2014, calling for a universal moratorium on executions, Canada joined the list of co-sponsors at the first opportunity in 2016. It has maintained consistent opposition to the death penalty since then.

How did the abolition of the death penalty affect Canada?

Canada and the United States shared a similar trajectory on the death penalty from the mid-20th century until 1976. Canada stopped carrying out executions after 1962 and, with some exceptions, had various moratoriums on the death penalty. In 1976, Canada’s parliament voted to abolish the death penalty from the Criminal Code.

From 1972 to 1976, the death penalty in the United States was deemed unconstitutional. In Furman v Georgia (1972), the Supreme Court found the death penalty “unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.” In Gregg v Georgia (1976), the Supreme Court ruled the death penalty could be revived in Georgia, Florida, and Texas and gave juries “sufficient discretion in choosing whether to apply it.”

Both countries, from about 1962 until 1976, saw a gradual rise in per capita homicide rates. This was attributed to the coming of age of the Baby Boom generation. Most violent crime is perpetrated by individuals from their late teens to mid-20s.

Starting in 1977, Canada’s per capita homicide rate began a gradual decline, to an all-time low of 1.76 per 100,000 people in 2018. The United States, on the other hand, did not see a constant steady decline in the per capita homicide rate. In 2018, the rate was 5 per 100,000 people. In recent years, it has declined.

Canada, as a result, is often cited as an example to demonstrate that the abolition of the death penalty, at the very least, does not cause an increase in violent crimes.

Amnesty International

GLOBAL DEATH PENALTY REPORT 2023

Amnesty International opposes capital punishment in all cases, regardless of the offender’s characteristics, crime, or method of execution. The death penalty violates the right to life and the right not to be subject to cruel or inhumane treatment or punishment. Read our annual global report on the death penalty.

Frequently Asked Questions

When was the last execution in Canada?

On December 11, 1962, the last execution in Canada took place at the Toronto Don Jail when Arthus Lucas and Ronald Turpin were both executed on murder charges. The last person killed by military execution under Canadian military law was Harold Pringle on 5 July 1945 in Italy.

When was the last death sentence passed in Canada?

On May 14, 1976, Mario Gauthier was sentenced to be hanged for the murder of Georges Nadeau, a painting instructor at the Cowansville Penitentiary in Quebec. The sentence was commuted when Canada abolished the death penalty for murder in Bill C-84 on July 27, 1976.

What crimes are punishable by death in Canada?

There are no crimes punishable by death in Canada. The last crimes to be punishable by death remained in the National Defence Act until December 10, 1998. However, no military executions have taken place since 1945.

How many people were executed in Canada?

From 1867 to 1976, there were 710 executions recorded in Canada. A complete listing of the death sentences and executions passed in that period was compiled by the National Archives of Canada.

Can the death penalty ever return to Canada?

No – not legally. In 2005, Canada ratified the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. This binding legal instrument prohibits countries from carrying out an execution and, by its design, has no legal means to withdraw. Furthermore, in 2001, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that even returning a prisoner to another jurisdiction where they may face execution is a violation of the Charter of Human Rights.

The last motion to return the death penalty was debated in Canada’s parliament in 1987. It was defeated by a vote of 148 to 127. The leaders of all major parties at the time opposed the death penalty but permitted members to vote freely.

Why did Canada abolish the death penalty?

Movements against the death penalty have been around since Canada’s founding. However, several factors influenced the substantial growth in abolition around the world.

Some high-profile cases of wrongful conviction and potentially wrongful execution brought particular attention to the hazards of a legal system that can result in execution. Two cases in particular were those of Steven Truscott and Wilbert Coffin.

Steven Truscott was sentenced to death at the age of 14 in 1959. Truscott’s sentence would eventually be commuted and much later overturned in 2007. Wilbert Coffin was executed on flimsy evidence and with the suggestion that the execution was made more for political motives rather than legal ones.

At the same time, the United Kingdom was also moving towards abolition, which took place in 1969. There was similar momentum in the United States. From 1972 to 1976, the death penalty was considered unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court.

Other factors undoubtedly influenced abolition, including the 1948 United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. The subsequent development of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights restricts the death penalty in those countries where it is still used for intentional crimes causing death (i.e., murder). Today, more than two-thirds of the world has abolished the death penalty in law or practice, with over half of the world’s countries abolishing it in law. Most executions today occur in just a handful of countries.

What is Canadian opinion on the death penalty?

When asked, Canadian opinion polling about the death penalty has produced varying results depending on which questions are asked. For example, “agrees with the death penalty for murder” or whether the person “wants to see a return of the death penalty.” Other factors, such as perceived levels of crime or high-profile cases, may also affect opinion polling. What’s more, opinions on the death penalty, in general, are often not realized when applied to specific cases.

In the United States, for example, to sit on a jury in a death penalty trial, jurors who are opposed to the death penalty are automatically disqualified. Despite this, just 21 death sentences were imposed in the entire United States in 2022.

Support for the death penalty in Canada in recent years has generally found a slight majority. However, these same polls have revealed that the arguments made in support have generally been debunked, misinformed or not proven.

There is no evidence showing the death penalty to have any unique deterrent effect on crime. Correlations of the homicide rate with executions indicate the opposite. There are more per capita homicides in jurisdictions with the death penalty than those without.

The death penalty is also more expensive than a sentence of life without the possibility of parole in a modern country (see the numerous studies posted by the U.S. Death Penalty Information Center for reference).