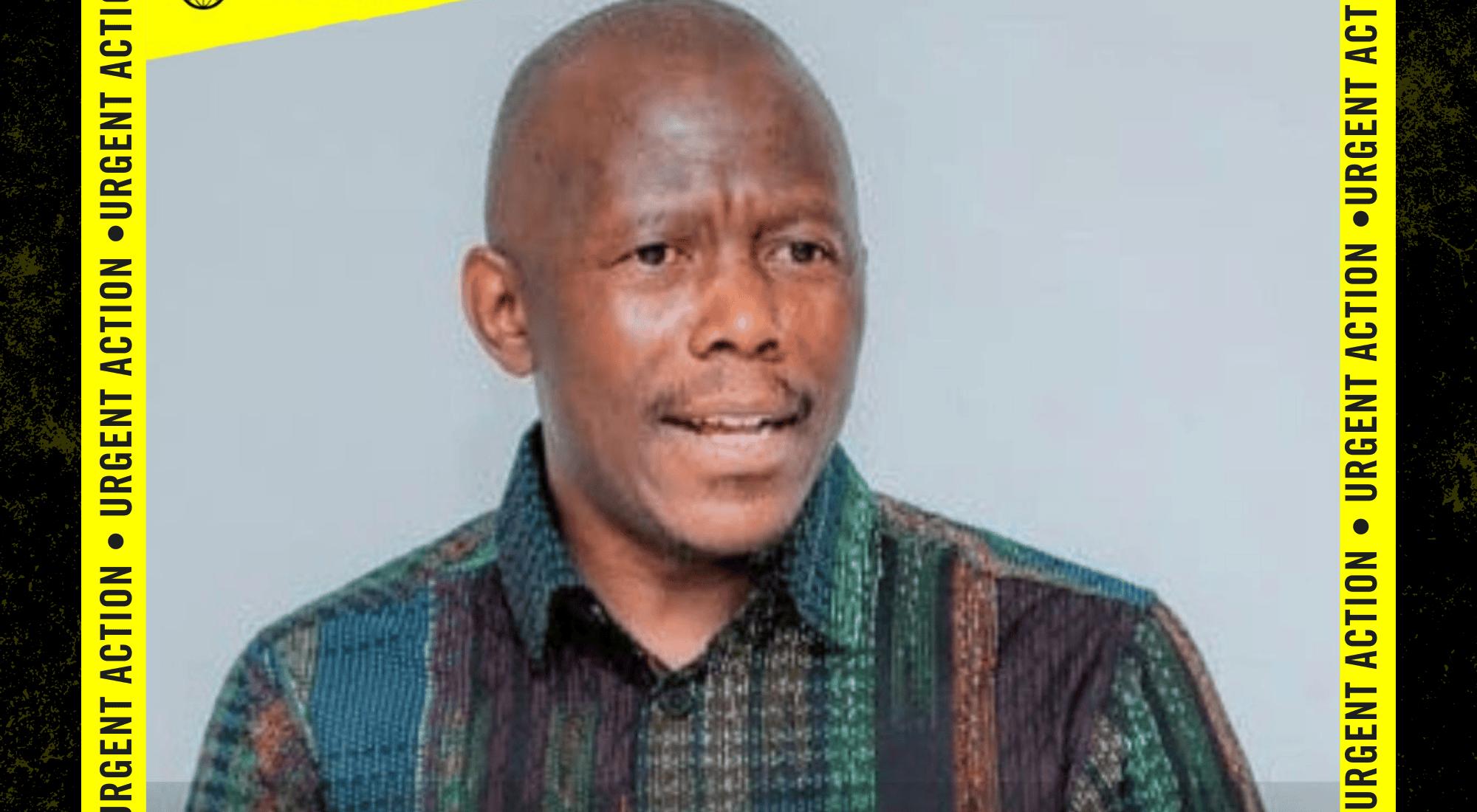

Brent Brewer is scheduled to be executed in Texas on November 9, 2023. His 1991 death sentence was overturned in 2007, but he was resentenced to death in 2009. In 1991 and again in 2009, the prosecution relied on unscientific and unreliable, but influential, testimony of a psychiatrist who asserted that Brent Brewer would likely commit future acts of violence, a prerequisite for a death sentence in Texas. Nineteen years old at the time of the crime, Brent Brewer is now 53. He has been an exemplary prisoner, with no record of violence during his three decades on death row.

Here’s what you can do:

Write to the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles urging them to recommend to Governor Abbott that he commute the death sentence of Brent Brewer.

Write to:

Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles

P.O. Box 13401, Austin, Texas 78711-3401, USA

Email: bpp_pio@tdcj.texas.gov

Salutation: Dear Board Member,

Background

Brent Brewer was sentenced to death after being convicted of the 1990 capital murder during a botched robbery of a 66-year-old man. He was fatally stabbed in his truck as he was driving 19-year-old Brent Brewer and his girlfriend (“KN”), 21, who had asked him for a lift. Weeks before the crime, Brent Brewer had been committed to a state hospital with depression and suicidal ideation. There he had met KN, who was in the hospital for drug rehabilitation treatment. In 1992, KN pled guilty to capital murder in the stabbing and was sentenced to life imprisonment.

In 2007, Brent Brewer’s death sentence was overturned because of inadequate jury instructions at the 1991 sentencing. At the 2009 resentencing, the defense put two mitigation witnesses, the defendant’s sister and mother, on the witness stand for a combined 28 minutes. A psychologist, who had been involved in the case on appeal in 1996, provided a report to the post-2009 appeal lawyers on mitigating evidence that could have had been presented in 2009.

At the time of the crime, he wrote, Brent Brewer “suffered from major depression, severe anxiety,” and “substance abuse, tied to his history of neglect, abuse, and family dysfunction”. He “suffered from brain dysfunction,” which the jury did not learn about, represented a critically important mitigating factor concerning Mr. Brewer’s judgment and decision-making capability. Abandonment fears were of particular importance in understanding Mr. Brewer’s behavior at the time of the offense, as was his dependent relationship with his co-defendant, [K.N.]”. Their relationship “helped to undermine his judgment and increase his impulsivity”.

In Texas, a prerequisite for a death sentence is a jury finding that the defendant will likely commit future acts of criminal violence. At Brent Brewer’s resentencing, the prosecution presented a psychiatrist (Dr C.) who testified he would likely commit future violence, the same as he had said at the 1991 sentencing. In 2009, he added that despite Brent Brewer’s lack of violent conduct during nearly two decades on death row, he still believed he would commit such acts in the future. As was the case in 1991, Dr C. had not met or evaluated the defendant. He testified by responding to hypothetical scenarios set by the prosecution, and opined that the defendant had no conscience, violence “doesn’t seem to bother him”, he would join a gang in prison, and had a “preference for a knife”.

The American Psychiatric Association’s position

As long ago as 1983, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) informed the US Supreme Court (USSC) in a Texas capital case that “the unreliability of psychiatric predictions of long-term future dangerousness is by now an established fact within the profession”. The Court did not dispute the APA’s assertion but placed its faith, “at least for now”, in the adversarial process “to sort out the reliable from the unreliable evidence and opinion about future dangerousness”.

Three Justices dissented, arguing that “when a person’s life is at stake…a requirement of greater reliability should prevail. In a capital case, the specious testimony of a psychiatrist, colored in the eyes of an impressionable jury by the inevitable untouchability of a medical specialist’s words, equates with death itself.”

Brent Brewer’s lawyers presented evidence of his good prison record but did not challenge the admissibility of Dr C.’s testimony before, or at a timely point in the 2009 proceeding. In a separate case on appeal in 2010, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (TCCA) found that Dr C’s testimony was inadmissible under Texas law because it was insufficiently reliable, and the trial judge should have excluded it after the defense objected and had a hearing.

That defendant was tried in 1990, had his death sentence overturned in 2007, and was resentenced to death in 2008. Dr C. testified in 2008 (as he had in 1990) that the defendant would pose a future danger even though he had a spotless disciplinary record during 17 years on death row. The TCCA said “we cannot tell what principles of psychiatry [Dr C.] might have relied upon because he cited no books, articles, studies or even other forensic psychiatrists… There is no objective source material in this record to substantiate [Dr C.’s] methodology as one that is appropriate…”.

Unreliable testimony

In 2011, the American Psychological Association and Texas Psychological Association filed a brief in the USSC in another Texas capital case at which Dr C. had testified. The brief asserted that “scientific research now reveals that unstructured ‘expert’ testimony on future dangerousness like [Dr C.’s], despite its lack of scientific basis, influences jurors more than opinions based on structured risk-assessment methods… These empirically demonstrated realities render the admission of testimony like Dr C. in capital cases especially problematic because they suggest a real risk of prejudice that cannot effectively be combated through tradition adversarial measures.”

In 2020, in another Texas capital case, a brief filed in the USSC by experts in neuroscience, neuropsychology and related fields said that “it was now “well-established that a human brain continues to undergo profound changes through adolescence and young adulthood… in the areas and systems that are regarded as most involved in impulse control, planning, and self-regulation… [I]t is scientifically impossible reliably to predict the future dangerousness of an offender who commits a crime while under the age of 21”.

Seventy-seven of the 583 people (13%) put to death in Texas from 1982 to 2023 were 18 or 19 at the time of the crime (in addition to 13 who were 17, before that practice was prohibited by the USSC in 2005). There have been 19 executions in five states in 2023: Alabama (1), Florida (6), Missouri (4), Oklahoma (3) and Texas (5). These five states account for 62% of the 1,577 executions in the USA since 1976. Texas alone accounts for 37% of the national total. Amnesty International opposes the death penalty unconditionally.